Perspective of a person who has conveyed the experiences of the A-bomb survivors

2021年08月13日

The original Japanese version of this article was published on August 3, 2021. It was translated into English by the author with editorial assistance by Dennis Riches, and the English version was published on August 13.

As this year’s Hiroshima’s Atomic Bomb Memorial Day (August 6) fell during the period of the Tokyo Olympics, there were calls for a moment of silence to be observed at the Olympic games, at 8:15 a.m. on August 6 - the time when the bomb was dropped.

According to the Tokyo Organizing Committee for the Olympic and Paralympic Games, the city of Hiroshima asked the International Olympic Committee (IOC) to call for a moment of silence for athletes on August 6th. Electronic signatures requesting a moment of silence were also collected, and on social networking sites, people were asking, “Why doesn’t the Olympics do it when all of Japan does it?” In response, the Organizing Committee announced that it would not respond to the call for a minute of silence.

Since 2006, I have been participating as an interpreter in the Hiroshima-Nagasaki study tour for Japanese university students and students of American University in Washington, D.C., which has been ongoing since 1995. On these tours I have been working to convey the experiences of A-bomb survivors through interpretation and translation. As an interpreter, I have conveyed the harrowing A-bomb experience and the determination of anti-nuclear peace activists such as Mr. Taniguchi Sumiteru, Mr. Nakazawa Keiji, Mr. Iwasa Mikiso and others who are now deceased. The voices of these people are still burnt into my mind.

However, I must admit that I have my doubts about the call for a minute of silence from within Japan during the Olympics.

Some may wonder why someone who has been involved in the Hiroshima and Nagasaki movements would make such a statement. For the past 20 years or so, I have also been involved in peace activities in China, the Republic of Korea, the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea, and countries in Southeast Asia, listening to the war memories of fellow Asian friends. I hope readers can listen to why I, with such experience, question the uniform call for silence among athletes from all over the world at the Olympics.

People observe a moment of silence at the time of the atomic bombing on the morning of August 6, 2020, at Naka Ward, Hiroshima.

People observe a moment of silence at the time of the atomic bombing on the morning of August 6, 2020, at Naka Ward, Hiroshima.I have lived in Canada for a total of 25 years. The first time was when I attended a secondary school there. I had the sense that it was important for Japanese people to convey the experience of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. However, during my study in Canada, I was confronted with the difference in the way people remember war in Japan and the way they do in other countries. My friends from the Philippines, Singapore, Indonesia, and other countries told me about the atrocities that the Japanese military committed during the war.

It was a great shock for me, as I had not learnt about it at all in Japanese schools. I realized that my understanding of the war at the time was very shallow and biased, limited to the damage that Japan had suffered.

After the modernization of Japan started in late 19th century, Japan expanded its empire throughout the Asia-Pacific region through colonization and wars of aggression with its heavily-invested armed forces in order to catch up with the Western powers. The air raids on Japan, including those on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, were massacres of civilians carried out by the U.S. in the final stages of the empire’s destruction, and there is no question of their criminal nature.

However, as I have held A-bomb exhibitions overseas and talked about history with friends of various backgrounds including Asian, European, and North American, I have come to believe that when Japanese people talk about Hiroshima, Nagasaki and the air raids, they must bear in mind the history of Japan’s brutal subjugation, forced mobilization and killing of people of Asia for more than 70 years, as well as the mistreatment of Allied prisoners of war for the three years and eight months, leading up to the atomic bombing.

IOC President Thomas Bach offers flowers and a moment of silence at the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, Hiroshima, July 16, 2021.

IOC President Thomas Bach offers flowers and a moment of silence at the Cenotaph for the A-bomb Victims, Hiroshima, July 16, 2021.People from all over the world come to the Olympics. There must be many among them who have inherited the memories of the Japanese military’s atrocities in their countries. I don’t think we can ask those people to have a minute of silence only for Hiroshima and Nagasaki victims.

For example, July 27th was the 68th anniversary of the signing of the armistice of the Korean War, in which millions of Korean people were brutally killed, on the peninsula that had been divided when the Japanese colonial rule ended. Most Japanese people are probably not even aware of this anniversary.

If Japanese society as a whole were already facing the history of Japan’s aggression head on, and maintaining a position, for example, to never forget the Korean A-bomb victims who suffered the atomic bombing under colonial rule, the meaning of the call for a minute of silence would be different. In such a case, visitors to Japan might spontaneously initiate such a movement without the need for the Japanese side to call for it.

However, Japan is a society where the government takes the initiative in denying the history of forced labour, where many members of the Diet visit the Yasukuni Shrine which glorifies the aggressive war, and where efforts to remember the Japanese military’s “comfort women” system get flooded with threats. The organizing committee for the 2020 Tokyo Olympics and Paralympics decided not to ban the use of the Rising Sun flag, which is a symbol of Imperial Japan that triggers the trauma of war for many people of Asia.

As an analogy to this situation, consider what the reaction would be if Germany were the host country of the Olympics, and Germans called for a moment of silence because the anniversary of the bombing of Dresden, which also killed tens of thousands of civilians, fell during the Games. With the Holocaust in mind, such a request would meet strong resistance in some countries, and Germany would not avoid criticism for portraying itself as a victim of war. Isn’t the same true in the case of Japan?

Some who have read this far may think that since the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were the first nuclear catastrophes brought to humanity, we should emphasize the universality of the bombings and separate them from Japan’s historical issues. In this regard, I would like to introduce an English translation of the panel about the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, at the National Memorial Museum of Forced Mobilization under Japanese Occupation in Busan, Republic of Korea, which I visited in 2019:

The first atomic bomb attacks on humanity occurred at Hiroshima at 8:15 a.m. on August 6th, and on Nagasaki at 11:02 a.m. on August 9th, 1945, three days apart, and one after another. As a result, hundreds of thousands of people were killed or injured, including many Korean farmers who had had to leave their homes under Japanese colonial rule, Korean conscripts who had been mobilized to work in Japanese munitions factories, and Allied soldiers who had been taken as prisoners of war by the Japanese military. Of the approximately 50,000 Korean victims of the atomic bombing in Hiroshima and 20,000 in Nagasaki, some 40,000 died without surviving beyond 1945, and of the remaining 30,000, some 23,000 are estimated to have returned home. Koreans, who accounted for about 1/10th of the total number of A-bomb victims, accounted for 57.1% of the deaths, which was much higher than the overall death rate of 33.7%. Japan has publicized the devastation in the two cities extensively and appealed to the whole world for peace and opposition to war. Peace and opposition to war are values for the co-prosperity of humanity. However, the meaning of these values change considerably depending on who says it. Before pronouncing against war and for peace, Japan should show its sincere remorse for its war atrocities and take responsibility for them. (Bolded part by author)

From the standpoint of a country that was subjected to colonial rule by Japan, I can fully understand the argument that Japan would be qualified to speak about universal values common to all human beings only if it sincerely reflected on and made amends for the past. For the Japanese to isolate the atomic bombings from their historicity while emphasizing their universality is tantamount to denying Japan’s perpetration of war. The nations victimized by Japan can never isolate the atomic bombing from the full historical context, and the perpetrator’s side should never force them to do so. It is only by putting oneself in the other side’s shoes that one can see the full context of such historical events.

Of course, there are many people on the Korean peninsula and in China who mourn for the victims of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki every year, whether there is an Olympics or not. They do so voluntarily, not because they are told to do so by the Japanese side. I think it is unreasonable to expect a uniform behavior from people who have not gathered for that purpose.

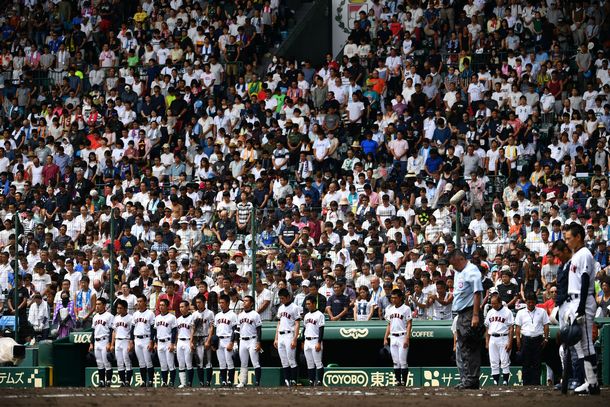

As sirens interrupt the game, baseball players of Konan High School, from Okinawa, take a moment of silence at Hanshin Koshien Stadium, at noon on August 15, 2018.

As sirens interrupt the game, baseball players of Konan High School, from Okinawa, take a moment of silence at Hanshin Koshien Stadium, at noon on August 15, 2018.For similar reasons, I feel uncomfortable with the sirens that go off at noon on August 15th at the Koshien high school baseball games every summer, forcing the entire stadium to be silent. Some Japanese high school students may have roots outside of Japan, and some may be Korean residents in Japan. It is not surprising if some of them are repulsed by the idea, wondering why they have to hang their heads on the anniversary of the day when one who was responsible for the war announced his surrender to the people in Japan.

For those who have ties to the countries ruled by Japan, August 15th is Liberation Day, a day to be celebrated. In the eyes of the Allies, it is the VJ (Victory over Japan) Day. It is the day when Japanese fascism collapsed, and peace returned to the Asia-Pacific region.

As I indicated at the beginning of this article, I share the same values as the people who call for the “August 6th Olympic Day of Silence,” in the sense that we mourn for the A-bomb survivors and try to realize a peaceful world without nuclear weapons and war. I hope that this essay will serve as a catalyst for dialogue and mutual understanding about historical consciousness.

有料会員の方はログインページに進み、デジタル版のIDとパスワードでログインしてください

一部の記事は有料会員以外の方もログインせずに全文を閲覧できます。

ご利用方法はアーカイブトップでご確認ください

朝日新聞社の言論サイトRe:Ron(リロン)もご覧ください